I spent an hour or so last night flipping through and re-reading parts of Good to Great by Jim Collins, the popular classic business book about the qualities that make companies successful. I first read the book over 5 years ago. That was a time when I began to pick up books on business with the goal of extracting lessons I could apply to Barrel.

I remember a specific part of the book that I took away at the time as a valuable lesson: Start a “Stop Doing” List

Most of us lead busy but undisciplined lives. We have ever-expanding “to do” lists, trying to build momentum by doing, doing, doing–and doing more. And it rarely works. Those who built the good-to-great companies, however, made as much use of “stop doing” lists as “to do” lists. They displayed a remarkable discipline to unplug all sorts of extraneous junk.

The big lesson here is that when you run a disciplined organization with a clear mission (“the Hedgehog Concept”) and goal (“the BHAG”), it’s possible to spot the activities that take away from what’s important. This is where a Stop Doing List comes in handy– we should question activities that do not seem to contribute directly to the mission and goal and work to stop doing them.

Five years ago, we didn’t have a clear mission or a goal. These were largely undefined, and I know that I personally lacked an understanding when it came to proactively developing an organization. Lacking the fundamentals, a book like Good to Great was bound to lead to cargo cult behavior, that is, I would replicate certain trappings of successful companies without actually understanding what made them successful in the first place.

I recently dug up a Barrel version of the Stop Doing List from early 2012 and reminisced the state of mind I was in back when we put this together. While embarrassing, I think it’s worth sharing an edited version to make the point that taking advice from a book without deeper thinking can lead to poor decision-making.

The Barrel Stop Doing List (Jan. 2012)

Stop…

- …running non-revenue producing media sites (sell or shut them down)

- …taking on website projects for under $XX,XXX

- …taking on large dev projects and projects with too many unknowns (custom apps)

- …offering social media marketing (day-to-day management, reporting, etc.)

- …taking on design and development of Shopify sites under $XX,XXX

- …working with clients who have undecided branding

- …working with clients who are poor at communication & do not pay on time

The first one was actually a good one. We had a number of websites that we had launched for fun but were a drag on our time. One was a gallery for Korean food recipes and another one was a review site of schools in Korea that taught English. We had employees work on these in-between client work rather than investing their time on professional development or streamlining internal processes for future client work. Shutting these down was definitely a timesaver, although that process was dragged out for quite some time.

The last one, #7, is also not too bad. We needed to vet our clients better and make sure they were both serious and had the money to engage with us. This meant having a process in place to qualify them during new business discussions and also making sure they would invest in having a point of contact who would see through projects. But once you have a good qualification process in place as well as a robust way of handling receivables, you don’t need something like this on a Stop Doing list.

When I look at #2 through #6, I can only shake my head. This is the list of someone who doesn’t want to figure out a solution but wants to make problems go away by declaring that we’ll run from them. I’ll dig a little bit deeper into these to show how I totally missed the point of this exercise.

#2 and #5 were the result of horrific project experiences where we went way over budget, the final quality was subpar, and the client was unhappy. The easiest thing to do was blame the small budget for the failure of the project. In retrospect, I think this mentality of “blame the low budget” made us less reflective about our process and the way we managed our clients’ expectations. If a project was doing poorly, it was because “the budget wasn’t high enough”, a cop-out phrase that we used to accept poor project outcomes.

#3 was also a reaction to unfortunate project experiences. We had worked on some ambitious builds that did not turn out well and resulted in cost overruns, client dissatisfaction, and team turnover. “Let’s stop doing big custom app projects” became the mantra. Instead of figuring out new processes and implementing frameworks to better scope, structure, and manage larger scale projects, we simply said no thanks and turned away a good amount of business. Perhaps the turning away was a good thing at the time in that it saved us more grief, but once again, there was little internal change that came about.

#4 and #6 came about because, rather than taking the time to experiment, codify processes, and have productive conversations with clients about how we can add value, it was easier to just say “let’s not do these things” and ignore the ways in which our clients would find value (esp. five years ago, when social and branding offered more competitive advantages!).

I only gladly engage in this self-flagellation knowing that our business has come a long way since. Here are some behaviors that demonstrate our progress:

- When we talk about new project engagements with clients, we always discuss the goals and the value the project is expected to create for our clients’ business. This allows us to think about pricing not as a unilateral budget but as an investment through which our clients can expect a good return. This line of thinking guides our recommendations and helps to build trust with our clients.

- We invest quite a bit of time critiquing and evolving our processes so that we can solve underlying issues that led to cost overruns, miscommunication, or any flaws in the final product. We also push ourselves to question existing processes and won’t hesitate to experiment with new deliverables that may get the job done better. What’s important is that we’re constantly in a state of experimentation and learning while understanding that what we deliver has to meet the expectations we set for our clients.

- Speaking of experimentation, we’ve made a commitment to developing new service offerings that draw on our core skill sets and bring value to our mission of helping our clients attract, convert, and retain customers. We’ve accepted the fact that rolling out new services requires lots of work, patience, and the ability to take setbacks in stride while trying to improve for the next opportunity. In just the past year, we’ve been able to roll out a suite of services that were non-existent and are now essential in our day-to-day discussions with our clients.

When I first read Good to Great, there were many things that were foreign to me. I remember coming upon the concept of the Flywheel and just breezing past it without much thought. This time around, I found myself lingering on it for a long time. In fact, I even watched some YouTube videos of what a physical flywheel was just to make sure I got the analogy right.

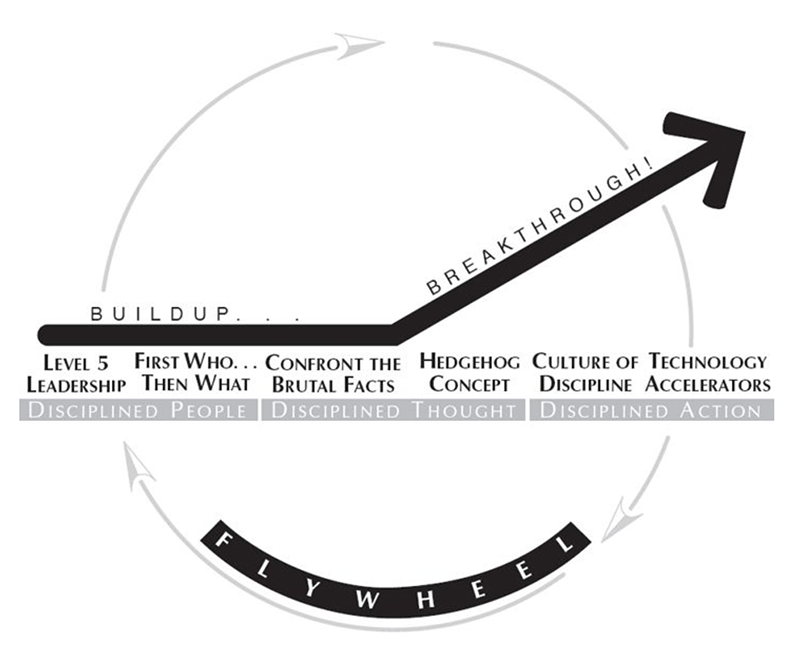

The Flywheel diagram is a great summary of Good to Great and a good high-level framework for thinking about business leadership. Looking back, I think the concepts in this book helped to prepare me for other business books later on, especially books that had very prescriptive frameworks with instructions on installing an “operating system” for running the business.

The Flywheel from Good to Great by Jim Collins. Five years ago, it was hard to appreciate how the full system worked, but these days, I can map almost every activity at Barrel to the diagram here.

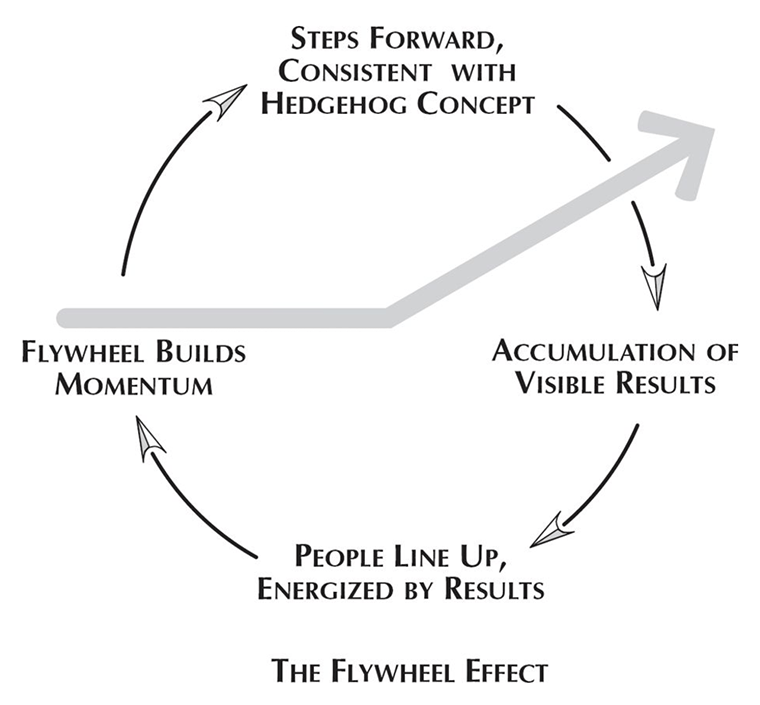

When I think about the day-to-day operations at Barrel and what I hope to achieve as a member of the executive team, the second Flywheel diagram, The Flywheel Effect, comes to mind. The mission-driven actions, both big and small, that accumulate into visible results, and the feeling of momentum that comes from successful project launches, expanded relationships with clients, and growth of the team in both skill and size–all these things create a certain energy which then build up towards what I hope will be a breakthrough. The two Flywheel diagrams are great reminders that at the end of the day, it’s the organization’s discipline (in people, thought, and action) that will allow for the continual build-up of momentum.

Getting back to an earlier point that I had–books are wonderful in that they introduce us to new ideas and concepts and force us to think about things in new ways. And in revisiting Good to Great, it was immediately apparent to me that the person who read this back in 2011/2012 was a very different reader than the one in 2017. I know that as I read more books and also experience new challenges and successes with the business, there will be future interpretations that will make today’s reading seem quaint, if not outright naive.